Eight years ago, my boss came up with the idea that officials could give presentations on their hobbies. I chose to speak about electric cars, as I had been following the topic for several years. My annual review of new models had already grown into a document nearly a hundred pages long. In 2016, dozens of new electric car models were launched. The collection included 89 of them.

That same year, I also found international news reports covering 113 electric vehicle models ready for production. At the time, a factual, photo-illustrated overview of a couple of hundred models came as a surprise to my colleagues. Aside from a few Tesla models, most people only knew about electric cars from Nissan and BMW – someone had seen BYD electric taxis in China.

Even then, companies like Audi, BAIC, Beijing Hyundai, Cadillac, Chery, Citroën, Dongfeng, Fiat C, Ford, Genesis, Honda, Hyundai, Jaguar, Kawei, Kia, Lichi, Mahindra, Maxus, Mercedes, NextEV, Porsche, Renault, Rimono, Rolls Royce, SAIC, Škoda, Toyota (in partnership with Chinese firms), Volkswagen, Volvo, Windbooster, Xinsheng, and many others were already on the path to electrification. Many of these names have since disappeared from the market, but a long list of new entrants has emerged – today, everyone who wants to stay in the game is working on electric vehicles.

The burden of being a pioneer

As an Estonian, it felt good to present our progress – by 2013, over 600 electric Nissan Leafs and Mitsubishis were already on the roads in progressive Estonia. To support them, ABB had installed 165 public chargers across the country, promoted as the world’s first nationwide charging network. But the success of being a pioneer backfired: in Estonia, electric cars came to be seen as small, underpowered, winter-fearing vehicles that only existed thanks to public subsidies.

The electric vehicle revolution didn’t arrive suddenly or overnight. While speaking at the opening seminar of TalTech’s major FinEst Twins project in late 2019, I couldn’t avoid mentioning the accelerating breakthrough of electric mobility. That year alone, 151 electric car models hit the market, and 238 more were introduced as production-ready. Most of them, of course, in China – Western car manufacturers weren’t yet worried about competition.

This summer, China’s car market “unexpectedly” reached a turning point: in both July and August, over half of all cars sold were electric. Some, to be fair, were hybrids with fossil-fuel backup engines.

The effects of China’s progress were felt even in Estonia. Because Chinese electric vehicles were saving around half a million barrels of oil per day, forecasts for rising oil demand didn’t materialize, and prices “unexpectedly” dropped. Alongside the rapid growth of electric cars, this was also due to a cooling Chinese economy and the strong sales of liquefied gas-powered trucks – this year, every fifth truck sold runs on gas. Electric vehicles in other countries also contributed to cutting fuel consumption, bringing the total daily savings to over a million barrels.

This summer, China’s car market “unexpectedly” reached a turning point: in both July and August, over half of all cars sold were electric. Some, to be fair, were hybrids with fossil-fuel backup engines.

In the summer of 2024, China shifted from being a car importer to an exporter; now, as the world’s largest car exporter, it ships more electric cars abroad than it imports vehicles of any kind | Photo: China News Service/CC BY 3.0 license.

Despite the rapid increase in the number of cars, the volume of fossil fuel consumed by passenger vehicles in China is no longer growing – in fact, it is set to start declining at an accelerating pace next year. Previously, the amount of fuel burned by cars continued to rise simply because the number of internal combustion engine vehicles was still increasing. Now, however, fuel savings are expected to speed up, helped by a new subsidy that allows polluting cars to be replaced with modern technology.

Norway as a success story in electrification

One of the best examples of what the future may hold is, as we know, Norway – where electric cars now outnumber petrol cars (yes, among all vehicles ever sold). In August, the share of electric vehicles sold without a fossil fuel backup engine reached 94 percent. Within a year or two, the total number of electric cars will surpass the number of diesel vehicles that were popular in the previous decade.

Thanks to the rise of electric cars, Norway’s fuel consumption will be halved within 4–5 years. By 2035 at the latest, fossil fuel use will broadly approach zero, although a small amount of horsepower will still depend on internal combustion for decades to come. The very last drops of fossil fuel can be replaced with biofuels, which already make up 17% of the mandatory motor fuel blend in Norway.

Due to forward-looking political agreements and the country’s wealth, Norway is a unique case when it comes to electric cars. Most of the world is still waiting for electric vehicle prices to fall below those of traditional cars. Technologically, producing electric cars is cheaper than the previous generation of vehicles; the question, as we know, is how quickly battery prices will fall.

In China, battery prices reportedly dropped by around 40 percent in a single year, more than compensating for the temporary price increases. At least smaller electric cars are already cheaper than their polluting counterparts. Price is indeed the main reason electric cars surpassed a third of total sales and, when including those with a range-extending engine, claimed the majority. (The term “range-extending engine” is not ironic in China’s case: especially from Li Auto factories, more and more electric cars are being produced with a small petrol engine that generates electricity. It’s a good solution for cities with limited access to charging stations.)

Technologically, producing electric cars is cheaper than the previous generation of vehicles; the question, as we know, is how quickly battery prices will fall.

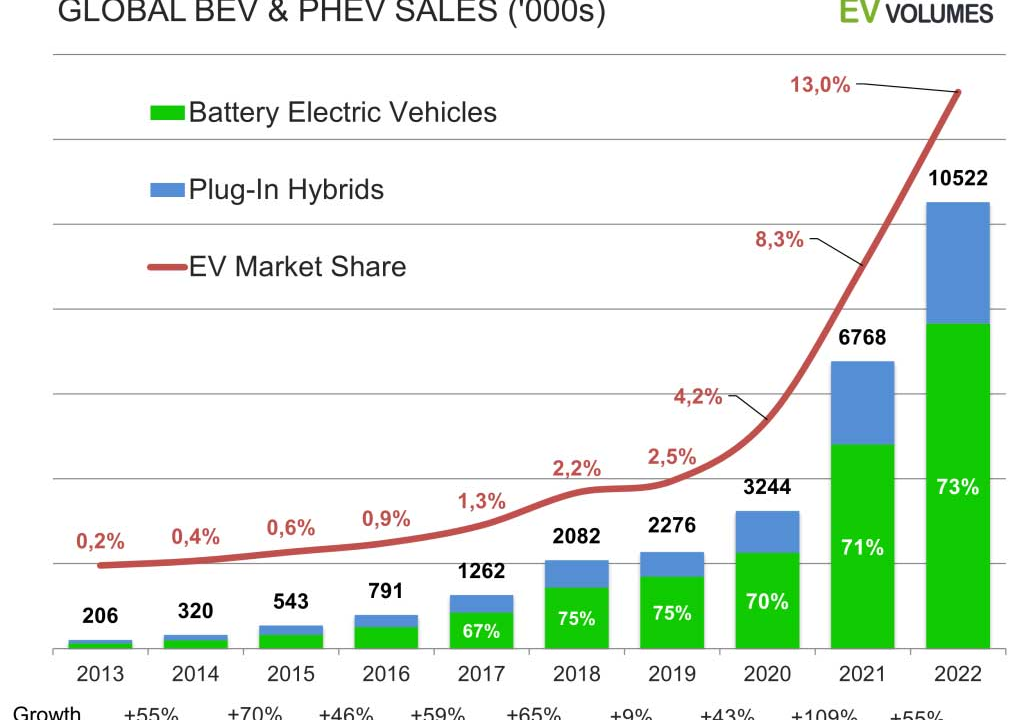

Chart of electric vehicle sales volumes from the database at ev-volumes.com.

Sales growth has slowed over the past couple of years – particularly in Europe, where countries like Germany, Italy, the UK, and Sweden have ended purchase subsidies. It may take two to three years for the growth rate of electric vehicles to recover, as prices gradually become competitive without state support. In any case, electric cars are becoming increasingly advanced from a technological standpoint.

The technological progress of electric vehicles is remarkably rapid, particularly in areas like higher-voltage architecture and faster charging. In recent years, major strides have been made in both battery quality and cost. There is a growing shift toward reliable, more affordable iron-based batteries.

At the same time, electric cars capable of covering over 1,000 km on a single charge are becoming available for long-distance drivers (the NIO ET7 was the first model to cross this threshold). Gotion – partly owned by Volkswagen and the operator of a new battery factory in Göttingen, Germany – is one of several manufacturers promising large battery capacities combined with 10-minute charging times. We can also expect continued improvements in battery performance in cold weather.

In the near future, artificial intelligence will increasingly support advances in materials and technical solutions. It’s expected to play a growing role in optimizing battery materials – the only question is who will implement improvements the fastest. In September, the head of CATL, the world’s largest battery producer, announced that their 20,000 R&D employees are already using AI to discover new materials that could unlock major innovations.

The massive R&D efforts of Chinese manufacturers

European carmakers have generally focused on perfecting quality rather than driving forward changes that might seem risky. European carmakers have tended to focus on endlessly refining quality and have been reluctant to lead changes that appear risky. The fastest-growing manufacturer, BYD, is now outpacing its competitors – likely including Tesla – not because of state subsidies, but because of the sheer scale of its R&D efforts. In July, BYD reported employing 102,000 people in research and development, adding over 5,000 new R&D workers each month in the first half of the year. For a company with ten times fewer developers – such as Tesla, with 10,000 to 13,000 – it is difficult to stay competitive.

European carmakers have tended to focus on endlessly refining quality and have been reluctant to lead changes that appear risky.

In July, Chinese carmaker BYD announced that it has 102,000 employees working in research and development | Photo: Michael Fortsch/Unsplash.

The final sentences of the European competitiveness report, signed by Mario Draghi, read as follows (free translation): “Our countries have never in the past seemed so small and insufficient in the face of challenges. Self-preservation has long been our concern. The reasons for a joint response have never been so compelling – and the strength for reforms we will find in unity.” Since the automotive industry is the most important sector of the most important EU member state, the first step must be to re-energize electric vehicle production (as cars are not produced in Estonia, chargers can be installed in front of every office and shop, as well as in the yard of every apartment association).

The global and especially European automotive industries have entered a very difficult phase, where traditional vehicles can no longer be produced for much longer, but electric vehicles cannot yet be produced cheaply enough. On top of everything, a large portion of jobs in the automotive sector are destined to disappear in any case. The paradox lies in the fact that manufacturing electric vehicles requires significantly less labor, and the transition means the loss of more than half of the jobs.

The reduction in the number of factory workers due to the mechanical simplicity of electric cars is only partially offset by the addition of developers. But those who do not transition to electric vehicles will fall behind competitors, as the future of the automotive industry is precisely the production of electric vehicles. Delaying the transition to electric vehicles will still lead to job losses. In China, European car manufacturers were indeed late, internal combustion engine production volumes are declining every month, and reportedly, this year none of the Western carmakers except Tesla has managed to make a profit in the world’s largest car market.

The rise of electric vehicles is comparable to solar energy

ERR has been diligently amplifying negative news about electric vehicles, of which there has indeed been no shortage in Europe in recent months. Some headline examples from September:

- “In Germany, electric car sales fell by 70 percent in August.” For comparison, the reference point was August of the previous year, when electric car sales were exceptionally high due to the announced end of purchase subsidies; for the same reason, in the first half of this year, electric car sales were 16% lower than a year earlier, whereas in Belgium, where subsidies continued, electric car sales increased by 48% in the first half of the year.

- “Battery manufacturer Northvolt cuts jobs due to slowing electric car sales.” The questionable prospects of this company already became apparent a year ago when it turned out that the company had only 4 confirmed patents; at the same time, i.e., in October 2023, the leading battery manufacturer CATL had 7704 confirmed patents. Where are Northvolt’s groundbreaking battery technologies?

Such local and temporary discouragements do not tarnish the general picture or the triumph of electric vehicles, even though dark messages are coming from Germany (in hindsight, there are plenty of internet sages who claim they foresaw what is happening now).

The rise of electric vehicles is comparable to the transition to solar electricity – in northern countries also to wind electricity – or to the emergence of batteries as the main players in storage. TalTech can uphold a reasoned and emotion-free approach to technological progress and avoid political and wishful thinking.

Those who do not transition to electric vehicles will fall behind competitors, as the future of the automotive industry is precisely the production of electric vehicles.

The media eagerly amplifies negative news about electric cars, of which there has indeed been no shortage in Europe in recent months. Pictured: a VW electric car in Amsterdam | Photo: Amber/Unsplash.

Even now, someone is buying polluting cars, and despite all aspects of technological progress, there will still be those in the 2030s who hum in their diesel cars: “I’ve tried to give you up, it seems a hopeless wish; in you I found everything, cared for nothing else.” Instead of bans, conservative buyers should have the option to purchase internal combustion engine vehicles even after 2035. Moreover, by the end of the century, one should still be able to hear the rumble of old cars at fairs and in automobile museums. It would be reasonable to demand bio-based and respectably priced new liquid fuels.

Instead of bans, conservative buyers should have the option to purchase internal combustion engine vehicles even after 2035.

The public sector vehicle fleet could be electrified

In terms of car age and pollution, Estonia is currently known to be at the tail end of the European Union, but this can be seen as an opportunity to transition to modern, affordable, clean vehicles in the new decade. Thanks to the rapid advancement and price drop of electric vehicles as a newer technology set, it is unlikely that Estonia will become an open-air museum of internal combustion engine cars. Economic or rational thinking is fairly widespread in Estonia due to general education levels.

Those with influence could advocate for the rationality – i.e., electrification – of the public sector vehicle fleet. If a private owner cannot afford to replace an old car with an electric one, it’s worth saving money and waiting for cheaper models. A new diesel or gasoline car will depreciate especially quickly, as in a few years the pool of potential (used) car buyers will shrink. A societal agreement on vehicles could go like this: the next car for both family and organization is electric. As a small step, one can already now choose an electric taxi over a polluting one and thereby accelerate the renewal of the taxi fleet.

Thanks to the rapid advancement and price drop of electric vehicles as a newer technology set, it is unlikely that Estonia will become an open-air museum of internal combustion engine cars.

Electric Dacia Springs delivered to the staff of the Nöörimaa care home in Võru County in July 2023 | Photo: Aigar Nagel.

Estonia’s national and Europe-wide opportunity is to connect electric cars to the power grid and reward vehicles for remaining connected during non-driving hours. Modern car batteries can easily withstand thousands of charge-discharge cycles and would balance renewable energy sources like sun and wind without major public investments.

If we take an average car battery capacity of 50 kilowatt-hours and multiply it by just a third of Estonia’s vehicle fleet – a quarter of a million – the result is 12.5 gigawatt-hours (GWh) of storage capacity. Car batteries can’t be fully discharged for shared use, so the usable storage capacity could be considered about half of the total, 6 GWh. That volume would exceed a hundredfold Estonia’s first large-scale battery (52 MWh), which Eesti Energia is building in Auvere.

Estonia’s electricity consumption last year averaged 22 GWh per day. If the battery being installed in Auvere covers just a few minutes of national consumption, then with just a third of the vehicle fleet electrified and grid-connected, car batteries would contribute five and a half hours of power per day. This would be a significant supplement to battery parks, covering half the storage need during the summer. After charging infrastructure is established, many electric car owners would have the opportunity not only to drive using electricity stored during cheap hours, but also to earn income by offering their storage capacity.

After charging infrastructure is established, many electric car owners would have the opportunity not only to drive using electricity stored during cheap hours, but also to earn income by offering their storage capacity.

As technological development accelerates, price competition in the car market intensifies. Affordable European electric cars would quickly find buyers, but such models do not yet exist (cars advertised as budget models are made in China – for example, the Dacia Spring is manufactured in a DongFeng factory). Whether it takes a few more years or more for Europe to bring its own affordable electric cars to market – the claim in the title remains unchanged.

One day, we will drive an electric car anyway. Without an auxiliary engine.