Those who remember life in the Soviet Union inevitably encountered the specter of nuclear war.

During the Cold War, the Soviet regime wielded nuclear threat rhetoric with sadistic regularity – on one hand instilling a deep anxiety about annihilation, and on the other creating a false sense of security: in the event of a nuclear blast, one was expected to quickly take shelter in the school cafeteria, don a rubber gas mask, and then carry on as if nothing had happened. That nightmare was hardly eased by the Chernobyl disaster – a very real horror story, which, bizarrely, could have ended even worse.

Against this background, it’s understandable why the idea of building a nuclear power plant in Estonia might provoke a visceral fear reaction in some people. The ongoing war of aggression by Russia – spiced with constant reminders of its nuclear arsenal and threats of its use – certainly doesn’t help alleviate those feelings.

Of course, one could immediately counter that emotional reactions are usually disconnected from reality. Chernobyl-style nuclear reactors are a thing of the past, and nuclear weapons posturing is (probably?) just rhetoric. On the other hand, neuroscientists have pointed out that affective emotional systems in the brain’s subcortical regions influence our behaviour more than we care to admit. Fear and the pursuit of safety are deeply embedded in human consciousness. Interestingly, while the Ministry of Climate’s nuclear energy working group has concluded that “the adoption of nuclear energy in Estonia is feasible” and aligned with climate goals for 2040 and 2050, it has also stressed the importance of “public support” – which could be read as an acknowledgment that the fears surrounding nuclear issues deserve to be taken seriously.

Still, even though affective impulses can’t be avoided and do matter in society, they shouldn’t dominate a strategically important public discussion. If we’re going to consider a decision as significant and consequential as building a nuclear power plant, we must begin by calmly gathering and examining all possible arguments – both for and against. Trialoog editorial team aims to begin that effort below.

1. Estonia’s small size

The first question that may arise is why a small country like Estonia would even need a nuclear power plant. A constructive answer could be that even a compact plant could meet the country’s entire electricity demand. It’s claimed that two reactors with a combined output of 600 megawatts would suffice. On the other hand, critics argue that if something serious were to happen, the whole country would be affected – we’d become dependent on a single source of energy.

2. Estonia’s geopolitical position

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has unfortunately proven that long-term national decisions must take into account the behaviour of our increasingly imperialist eastern neighbour. Would a nuclear power plant make Estonia too vulnerable to foreign threats? That’s a question with no simple answer. Politician Züleyxa Izmailova put it bluntly: “If there were a nuclear explosion, Estonia would essentially cease to exist” (ERR, Jan 15). The counterargument is that any attack on Estonia and/or Finland would also threaten Russia’s own territory – particularly a major centre like St. Petersburg. To put it bluntly: an attempted murder could also be a suicide attempt. Energy independence is another strong argument in favour of a nuclear plant.

3. Estonia’s geology

A scenario like the Fukushima disaster is nearly impossible in Estonia due to the region’s geological stability. As a humorous old rhyme goes, “Estonia is so small / we don’t even have a volcano” – in the context of nuclear energy, that’s a definite plus. The long coastline offers multiple siting options – from northern Estonia to Saaremaa. And Estonia’s relatively sparse population means a plant could be located in a place where only a few homes would even see it. Still, even that view might not sit well with anyone but the most stoic of souls.

4. Safety

This brings us to one of the most sensitive issues – how safe is nuclear energy? On the positive side, third-generation reactors are incomparably safer and more environmentally friendly than Chernobyl-era technology. (Though if you really want to compare, it’s like putting Piibeleht’s flying machine next to an Airbus A350 – they technically share a purpose.) Reactor lifespans are also improving, with third-generation reactors lasting up to 60 years. And since nuclear energy has caused major accidents in the past, huge investments have been made to improve safety – current statistics suggest about twenty accidents per 100 million reactor-years.

However, one could argue that no matter how safe nuclear energy is, radioactivity remains a phenomenon that is unimaginably difficult to control in the event of a serious incident – you can’t just “clean up” radiation like regular waste. The long-lived nature of radioactive waste is also a concern: it must be kept isolated from the biosphere for hundreds of thousands of years. The counterargument that this waste doesn’t have to be stored in Estonia feels partial – and somewhat hypocritical. But it’s also fair to note that waste management technologies are improving along with reactor efficiency, and the amount of waste generated per person is extremely small.

In some ways, nuclear energy is a bit like flying – the statistics keep improving, but the vague fear remains, because when something does go wrong, the consequences are final. Safety improves, but never reaches 100%.

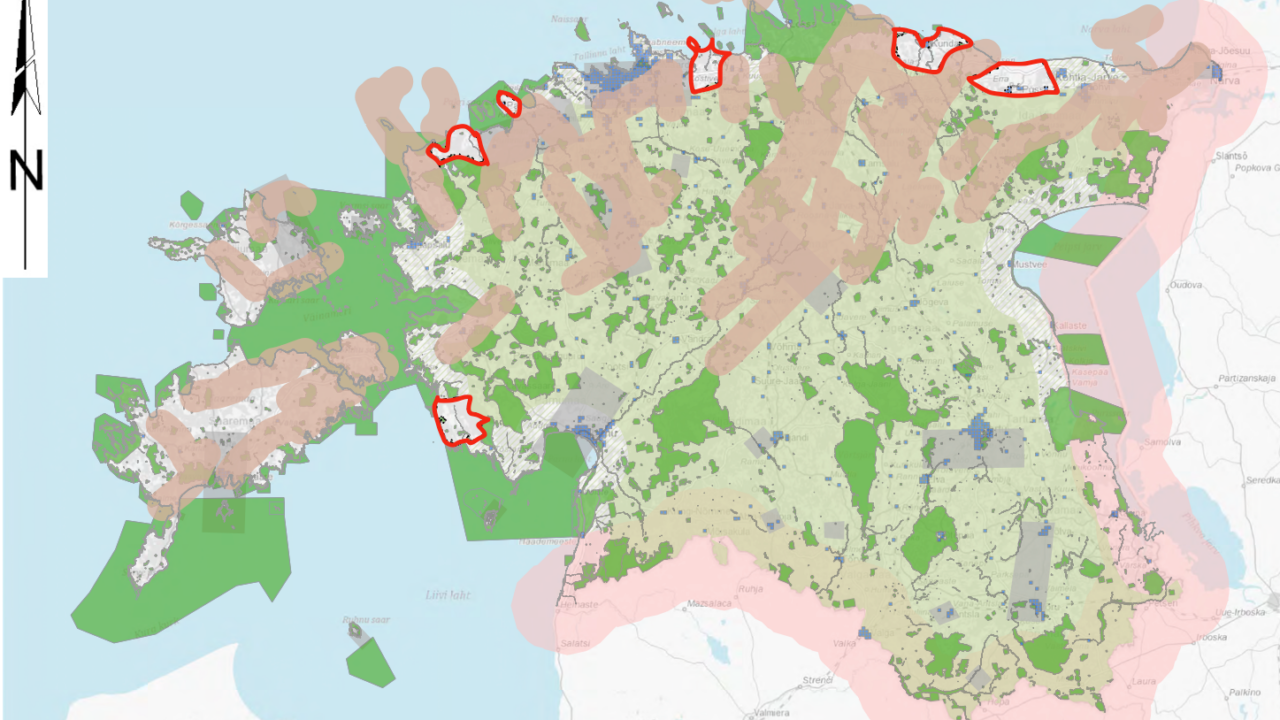

According to Fermi Energia, the most promising locations for building a small modular nuclear reactor are the northeastern coastal areas of Estonia | Image: Fermi Energia

5. Environmental friendliness

This point partly overlaps with safety – again, one can refer to the issue of storing radioactive waste. Additionally, an increasingly unstable climate may pose unexpected challenges. Still, statistics show that nuclear energy qualifies as a green energy source, largely due to its low carbon emissions. In terms of CO₂ output, only hydropower beats nuclear. A nuclear plant does not release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

There’s also the question of the resources required to build a nuclear power plant, but that line of argument risks slipping into a broader, unsolvable debate about the global interdependence and rigidity of modern supply chains – resource intensity is simply part of the system. In nuclear energy’s favour, however, is its ability to provide a steady electricity supply, unlike wind and solar, which are weather-dependent. True, excess solar and wind energy can be stored for later use, but this brings the reality of Estonia’s climate into play – where the sun is often a rare guest. In terms of balancing energy output and environmental sustainability, nuclear energy remains a serious contender.

6. Novelty

The closest nuclear plant to Estonia is in Sosnovy Bor, between Narva and St. Petersburg. One could argue that Estonia has been lucky – the plant, originally based on the Chernobyl design, has seen no major or lasting incidents. In support of a potential Estonian plant, it can be said that nuclear technology hasn’t evolved in a vacuum; its improved safety and efficiency are the result of years of scientific work and discoveries.

Moreover, designing and constructing a nuclear power plant would give a boost to Estonia’s research sector and likely generate new high-tech solutions. The plant would take roughly a decade to build – a long time by the pace of modern science, which moves in seven-league boots. Of course, a sceptic could counter that Estonia’s lack of experience with nuclear energy might negatively affect the final outcome.

*

There will likely never be full consensus on nuclear energy. But one must believe it’s possible to thoroughly weigh all arguments – for and against – and make a decision where the pros outweigh the cons. Trialoog will do its best to ensure that such an important debate moves not only in the right direction but also at the right pace – with clarity, balance, and evidence-based reasoning