Energy labels on apartment buildings have received considerable public attention–and rightly so. To assess the link between energy label ratings and actual energy costs, I selected four typical cases from the market.

Although the energy label includes detailed energy consumption data, the kilowatt-hour numbers mean little to the average buyer. What most people really care about is the average monthly energy cost per square metre of apartment space, in euros–covering both electricity and heating. To get that number, one needs to calculate the total residential and commercial floor area from the building’s plans, extract electricity and heat data from the energy label, apply energy prices, and then calculate the energy cost per square metre. Multiply that by your apartment’s size (including a share of the heated common area), and you’ve got your figure. All of this information is public, but it’s a hassle–future labels should simply state the monthly energy cost per square metre in euros.

In the following, I’ll translate the rapid progress in energy efficiency into euro terms for users. For developers, every euro matters, and investing in energy efficiency means additional cost. As a result, construction typically adheres closely to minimum requirements—requirements that are, in theory, based on optimal 30-year life-cycle energy efficiency.

The standards implemented already in 2013 ensured quite solid performance. Considering permit timelines and construction durations, it’s safe to say that apartment buildings built after 2015 should be a reliable choice for buyers—meaning energy performance won’t disappoint. Compliance with current requirements is the basis for fair competition, and today we’ve largely achieved that. I would even generalize that Estonia is now building apartment buildings with unprecedented construction quality. This is supported by a study commissioned by the Consumer Protection and Technical Regulatory Authority (TTJA) and conducted by TalTech, which reviewed 104 new apartment buildings and found consumer deception only in a very small number of cases.

New apartments today typically carry A or B energy labels–and soon, mostly A, once projects with pre-2020 permits are completed. However, a new apartment can come with a surprise cost. Reflecting car-centric planning, the city of Tallinn requires more parking spaces than apartments. In the city centre, this means underground parking, usually in a heated garage. For the buyer, one parking spot adds about €20,000 to the purchase. These large garages are typically heated to 16°C. For my case examples, I selected new A- and B-rated apartments in central Tallinn with heated garages, and compared them to older apartment buildings in areas like Mustamäe or Annelinn. All scenarios are based on a 65 m² apartment.

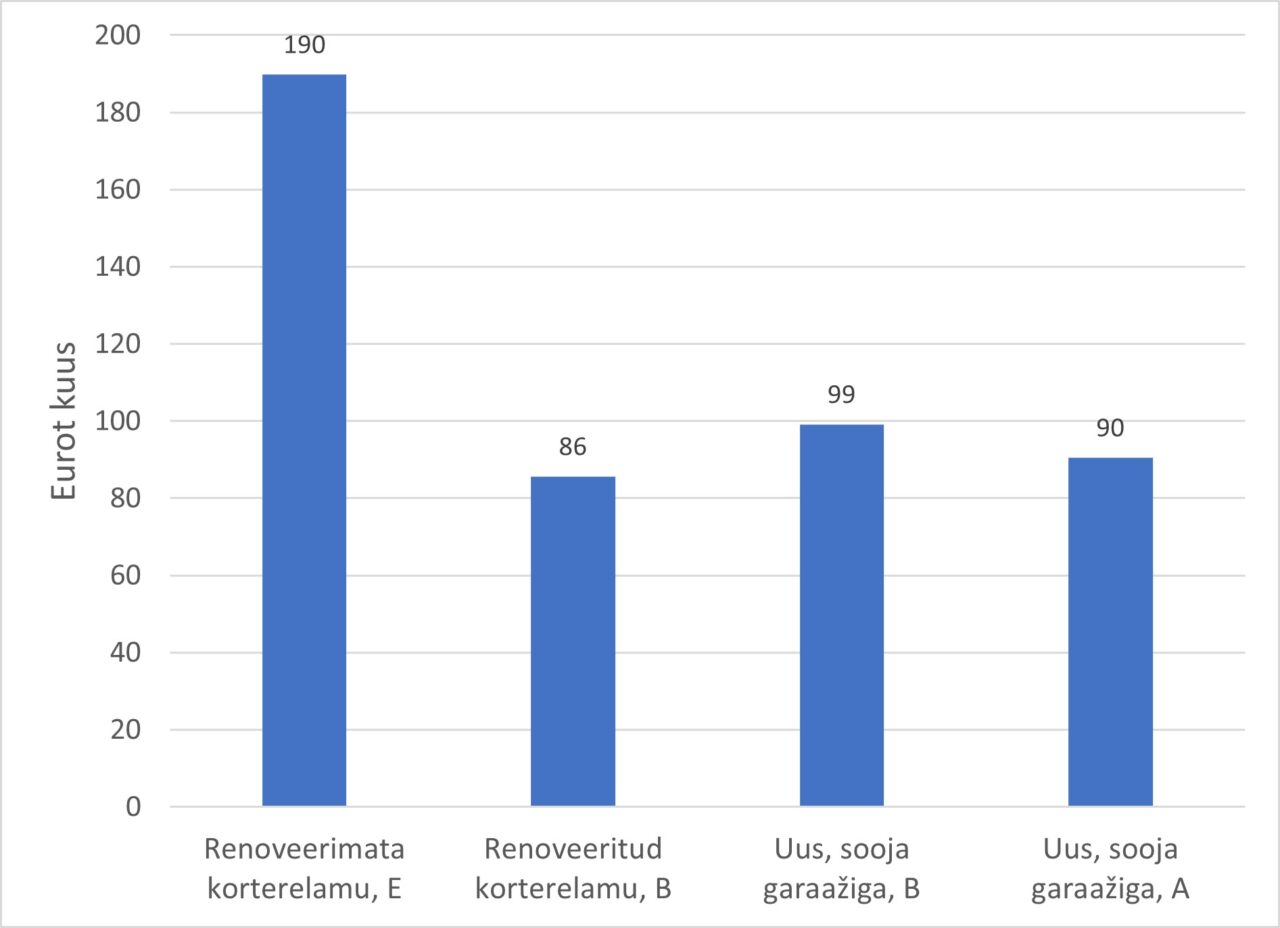

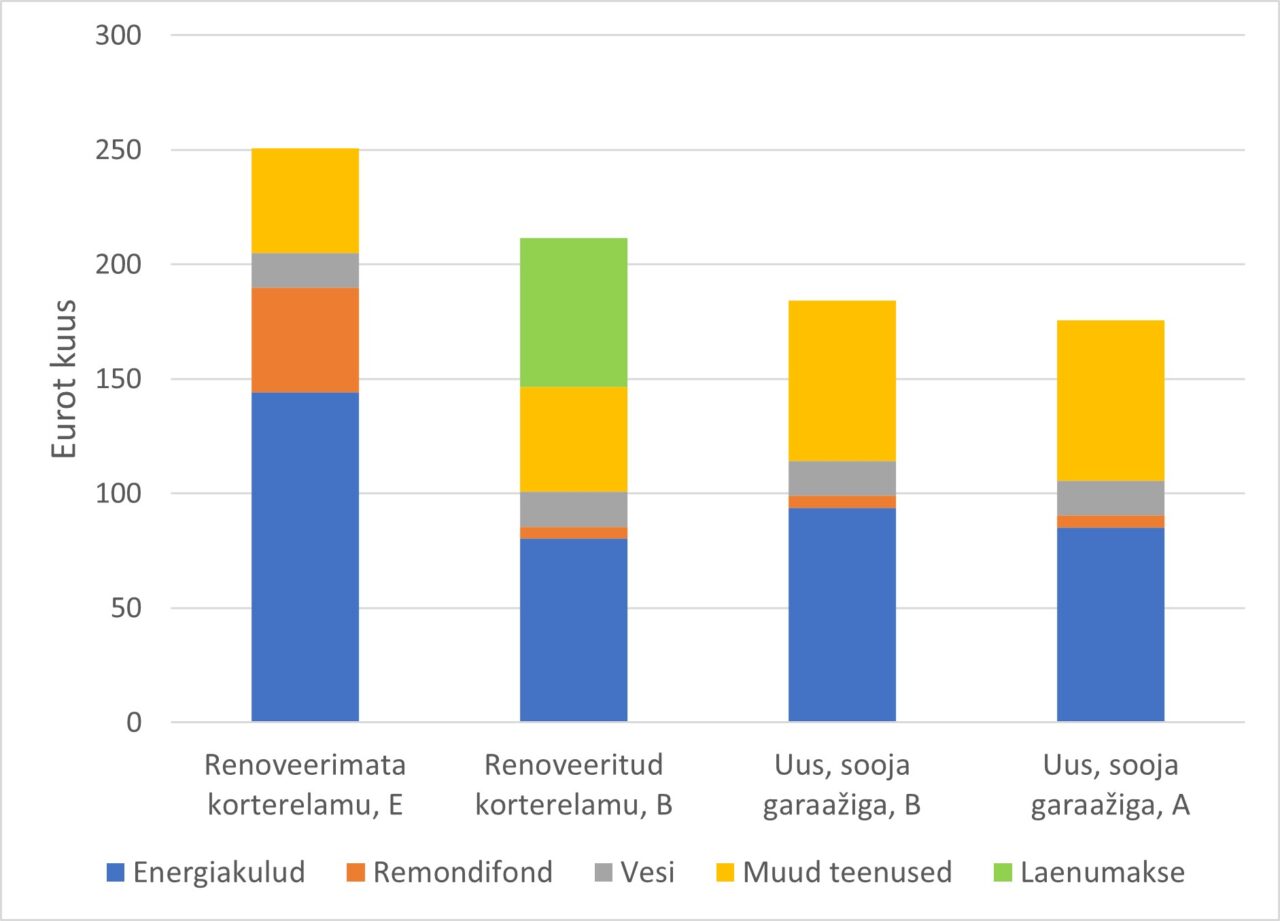

The baseline example, an old five-storey E-rated apartment block in its original state, has the highest costs. Monthly payments for energy and maintenance total about €190 (see Figure 1). This includes a maintenance fund of €0.70 per square metre. If such a building is fully renovated to B level under today’s practices, more than half of these costs can be saved. Assuming a post-renovation maintenance fund of just €0.08/m², the average combined cost for energy and maintenance would drop to €86 per month. The building’s relatively compact volume and modest window sizes help keep costs low. However, one must also consider renovation loan repayments. For buildings renovated a few years ago, the repayment might be around €65/month for a 65 m² apartment, but with current renovation prices and interest rates, this could reach €170/month.

New apartments on the market today come with both B and A class energy labels. Buildings with earlier construction permits are subject to B-class requirements, and in reality, the only difference from A-class is the absence of a solar power system. Assuming the building is heated via district heating, there’s no difference in heating costs—but A-class buildings have lower electricity expenses. This distinction is visible in the chart: the total monthly cost for a new B-class apartment with a heated garage is higher than for a renovated apartment building, averaging €99 per month. In the case of A-class, the cost decreases but still remains slightly above that of a renovated building.

In all cases, the energy costs and maintenance fund are accompanied by additional monthly charges: cold water at around €15, and administrative, maintenance, cleaning, insurance, internet, and security services—ranging from €45 to €70 per month depending on the number and level of services provided. The lower end of that range applies to older buildings with fewer services. Since the number of different utility and housing-related cost categories has grown, Figure 2 presents the total monthly costs for each apartment as a single summarized number.

The results from the example calculations can also be compared with other types of apartment buildings. For instance, if a new A-class apartment building doesn’t include a heated garage, its energy costs may actually be lower than those of a renovated building. In general, for newer buildings (constructed from 2015 onward), monthly energy costs including the maintenance fund should stay close to €100. Older dwellings, however, often reveal a crucial difference in quality: the absence of heat recovery ventilation. In such buildings, fresh air enters through vents above the windows–bringing with it cold air, noise, and fine particles. In smaller apartments, this can create an acute problem with drafts and cold air, while in larger spaces with fewer windows, the system performs somewhat better.

An example of how construction has strictly followed regulations can be seen in apartments built in 2013–without heat recovery ventilation and carrying an E-class energy label. From the outside, these buildings may appear almost new, but in reality, their energy costs can rival those of unrenovated Soviet-era blocks in Mustamäe. It should be noted, however, that this cost parity assumes heating is minimized in the old buildings, meaning the level of thermal comfort is not comparable.

In summary, the lowest energy costs are, perhaps surprisingly, found in comprehensively renovated apartment buildings. In addition to low costs, they offer the major benefit of heat recovery ventilation–a feature that may be missing in buildings constructed before 2015. New B- and A-class apartments are high quality and energy efficient enough that even large underground heated garages don’t significantly raise their overall costs. While buildings constructed from the year 2000 onward may look modern, they don’t necessarily perform well in terms of energy expenses. In fact, buildings constructed before 2015 are often the most unpredictable–they may show energy costs as high as 50-year-old unrenovated blocks.

What can we learn from this comparison? To exaggerate a little, the apartment market for buildings constructed before 2015 is something of a minefield. While energy labels are legally required, they are often missing–meaning it’s impossible to make an informed purchasing decision without thoroughly reviewing the building’s utility costs. And even when the label exists, calculating the number that actually matters to buyers–monthly energy cost per square metre–takes quite a bit of work.

That’s why it would make sense to propose two changes:

- Energy labels should be valid for no more than five years.

- They should clearly state energy costs per square metre in euros.

Since the energy label for an existing building is based on actual consumption data, a digital country like Estonia could and should automatically generate such labels for all apartment buildings.