Europe’s rivers are teeming with unseen struggles. With over a million barriers like dams and weirs fragmenting waterways, freshwater biodiversity is in a steady and rapid decline. Fish can’t reach spawning grounds, migration routes are blocked, and generations of aquatic life are shrinking. Traditional methods like electrofishing or physical traps fall short when it comes to capturing the complexity and diversity of these underwater ecosystems.

“Most times there’s not even cellular connection to these remote sites,” said Jeffrey Tuhtan, professor at TalTech Department of Computer Systems and head of the fish monitoring project. “Until now, it was practically impossible to monitor the majority of European rivers in real-time.”

“Until now, it was practically impossible to monitor the majority of European rivers in real-time.”

To tackle this, TalTech’s team developed two complementary innovations: ExoFish, a stainless steel, cone-shaped camera device installed in river barriers, and FishTube, a flexible AI-based software system that can run on existing and new digital underwater camera systems, making it cost-effective add-on for the hundreds of existing camera systems installed across Europe. Thanks to the TalTech innovation, camera systems can now process data on-site, removing the need for constant cloud connections and enabling real-time fish identification in some of Europe’s most remote rivers.

Seventeen FishTube prototypes are already being tested across Switzerland, Germany, and Sweden, where they’re running AI algorithms directly on the cameras themselves – a groundbreaking shift that saves time, power, and manpower in areas often too remote and dangerous for traditional data collection. “This is allowing biologists to monitor fish populations in places that were literally impossible to monitor before, especially during seasonal high flows caused by heavy rainfall or snowmelt” Tuhtan explained.

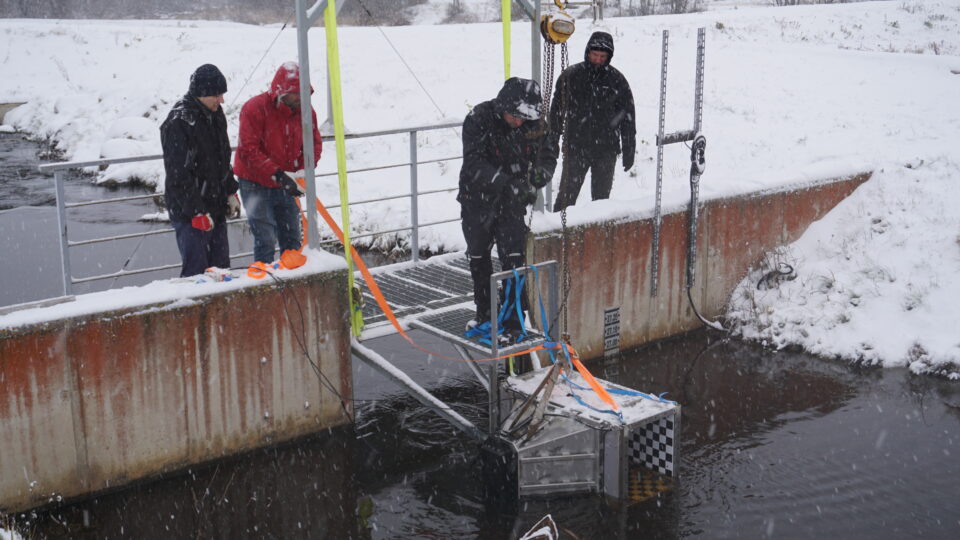

One of the aims of Perks’s visit was to exchange experiences. When the TalTech team asked him what he would need for underwater filming here, his list included diving weights, a rope, and pantyhose. Photo: Gert Zavatski

From YouTube to riverbanks

Despite having collected over 40 terabytes of aquatic footage, TalTech lacked rare species data essential for training their AI. That’s when Tuhtan stumbled upon Jack Perks’ extensive video library on YouTube. “I emailed a bunch of underwater wildlife YouTubers, and everyone told me to go away,” Tuhtan recalled. “Jack was the only one who replied, he was both amused and genuinely curious about what we were doing.”

“I emailed a bunch of underwater wildlife YouTubers, and everyone told me to go away. Jack was the only one who replied, he was both amused and genuinely curious about what we were doing.”

At first, Perks wasn’t entirely sure what to make of the offer. “Jeff just messaged me saying he wanted to use some of my footage for an AI project,” Perks remembered. “I didn’t think much of it at the time – I get a lot of unusual requests.” But when a follow-up message came inviting him to Estonia to see the system in action, his curiosity was piqued.

With over a decade of experience filming elusive fish species, Perks had amassed a unique archive – one that turned out to be invaluable for training the FishTube AI to recognise and differentiate between species in underwater footage of natural river environments. “I think my footage turned out to be pretty useful,“ he said modestly. “It kick-started the whole process – they needed examples of fish that just aren’t easy to capture in the wild anymore.”

The collaboration that began as a long shot evolved into a hands-on partnership – one where Perks’s fieldwork directly shaped how the AI sees and understands the aquatic world.

The pantyhose revelation and other field lessons

When asked what he needed for filming in Estonia, Jack listed divers’ weights, rope – and pantyhose. “I looked at him like he’d lost his mind,” Tuhtan admitted. But the idea was simple and effective: fill pantyhose with fish food, place them near the camera, and wait.

“The pantyhose let out a slow, continuous release of scent and small particles,” Jack explained. “That draws in small fish, which then attract bigger fish – and suddenly, you’ve got an active scene right in front of the lens.”

This method turned out to be one of the most valuable takeaways for the team. “We realised we’ve been chasing fish around instead of letting them come to us,” Tuhtan said. “It’s about changing the logic of our approach, and will save our group a lot of time in the future.”

Jack’s expertise also helped TalTech’s engineers understand optimal camera placement. “They’re thinking about wiring and hardware,” Perks said. “But I’m thinking about water flow, light direction, and fish behaviour – where the fish are likely to be and why.”

The event called “Fish and Chips,” which attracted students interested in natural sciences and technology, vividly demonstrated how a passion for nature can lead to meaningful scientific impact. Photo: Gert Zavatski

Inspiring future fish tech enthusiasts

Beyond sensors and species identification, the visit had a broader educational goal. Tuhtan wanted local students to see that working with AI doesn’t mean being glued to a screen.

“Young people often think they have to choose between IT and natural sciences,” he said. “But we’re showing them that they can combine both – that machine learning can help protect nature, not just optimise some tech business.”

“Young people often think they have to choose between IT and natural sciences. But we’re showing them that they can combine both – that machine learning can help protect nature, not just optimise some tech business.”

Perks’s talk, which drew in students already inclined toward ecology and tech, gave a concrete example of how passion for the outdoors can lead to scientific impact. Helena Carmen Udu, a TalTech BSc student research assistant in Tuhtan’s research group shared her own journey, having started out in high school and is now working as part of the TalTech team on developing cutting-edge machine learning models for fish biodiversity monitoring.

As Perks put it, “There’s always going to be a market for the real thing.” And by blending real-world experience with AI, TalTech and its collaborators are making sure the future of fish photography – and fish conservation – is both innovative and deeply human.