The memorandum signed in early September between Russia and China on the Power of Siberia-2 (PoS-2) pipeline marks a strategic shift in energy and geopolitics. Complementing the existing Power of Siberia-1, PoS-2 is expected to redirect around 100 billion cubic metres of Russian gas eastwards – reshaping China’s bargaining position and potentially influencing Europe’s liquefied natural gas (LNG) markets. This article examines what PoS-2 could realistically deliver in terms of flows, pricing and financing, and considers its implications for the European Union as well as potential policy responses relevant to Estonia.

PoS-2: what was agreed and what remains unresolved

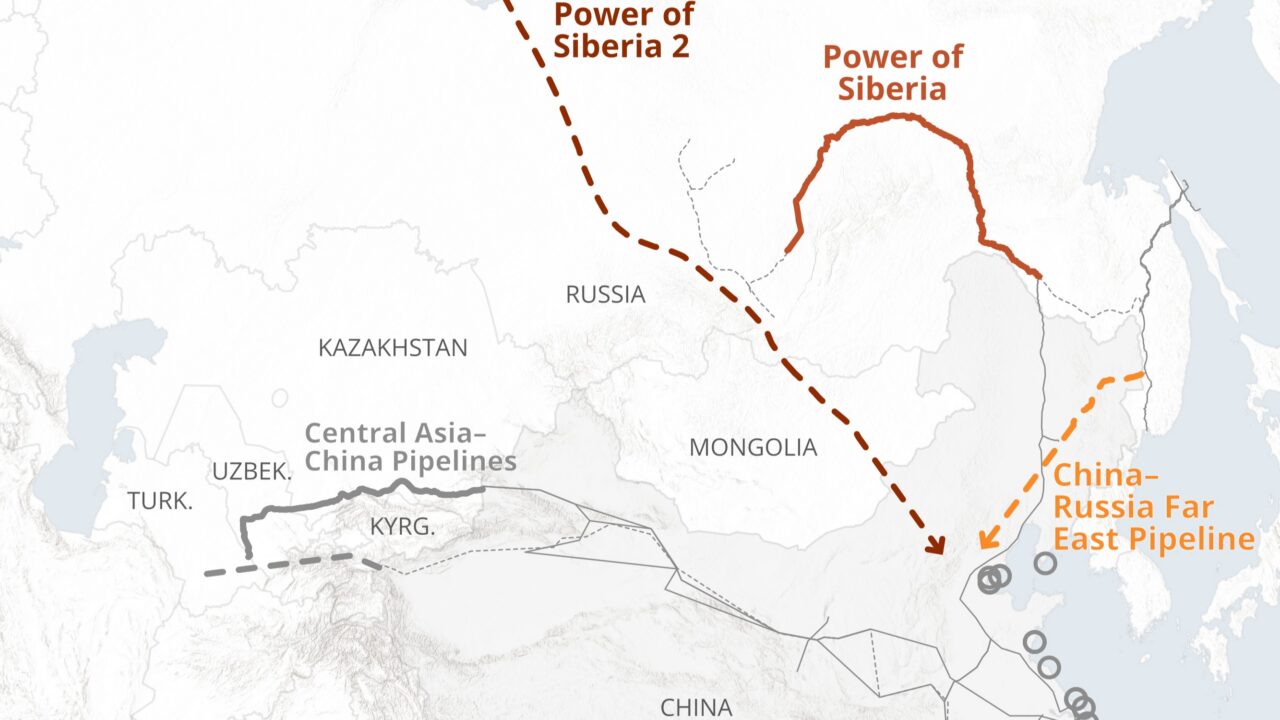

The political memorandum signed in September commits both parties to construct a pipeline that would channel gas from Western Siberia to northern China via Mongolia, with a planned annual capacity of around 50 billion cubic metres. At the same time, it was announced that the capacity of the modest Power of Siberia-1 pipeline would be raised to roughly 31–38 bcm in the near future, while throughput on the Far Eastern route from Sakhalin would increase from 10 bcm to 12 bcm per year. Gazprom described the document as legally binding at the project level but made clear that commercial terms – including the pricing formula, take-or-pay clauses, confirmed upstream field allocations and the financing package – remain subject to further negotiation.

Despite the remaining uncertainty, the project is already reshaping the positions of others at the negotiating table. The memorandum secures a long-term option for China and will likely strengthen Beijing’s position in price talks with LNG suppliers across the Atlantic. For Russia, PoS-2 offers a way to underscore its reliability as a major supplier and diversify export routes – although at the cost of deepening dependence on a single, extremely large buyer, introducing a structural asymmetry. It is also improbable that Russia will gain the same economic benefits from PoS-2 as it once did from exporting gas to the EU. The memorandum may thus confer strategic advantage on Beijing and strategic cost on Moscow: if pricing terms are unfavourable or China limits its offtake, political leverage could turn into economic vulnerability.

The political memorandum signed in September commits the parties to build a pipeline that would channel gas from Western Siberia to northern China via Mongolia, with a planned capacity of around 50 billion cubic metres per year. Illustration: Global Energy Monitor

Supply flows and LNG markets: one possible scenario

PoS-2’s significance lies above all in its timing, as it is expected to come online just as China’s long-term LNG contracts begin to expire. Between 2021 and 2024, Chinese companies secured long-term deliveries amounting to roughly 90 bcm of LNG, most of which will lapse around 2030–2033. PoS-2 is scheduled to start precisely then, giving Beijing the option to play LNG exporters off against Russia. This would strengthen China’s bargaining power at a moment when it remains one of the world’s largest gas importers. Decisions taken in Beijing during this period will shape not only Asian LNG prices but the entire global gas balance.

A second key factor is the future of LNG supply. The LNG market is entering its third and easily its largest growth cycle. Qatar alone plans to raise production from today’s 77 million tonnes to 142 million tonnes per year by 2030, with much of that future output still uncontracted – suggesting that significant volumes could reach the spot market.

One plausible scenario is that Qatar could deliberately saturate the spot market to undercut smaller competitors, sharply pushing down Asian LNG prices. Under certain circumstances, the European Union could indirectly benefit from such price declines – even if the gains originate in other regions.

However, Qatar’s strategy also risks severely disrupting the market before new capacity comes online, particularly if it coincides with market perceptions that China is exerting pressure around PoS-2. The combined effect could send powerful signals to LNG projects still awaiting final investment decisions this decade, causing investors to hesitate or even walk away, including from projects primarily intended to serve European buyers. This points to the realistic possibility that PoS-2’s knock-on effects may directly influence the EU’s supply security.

The LNG market is now entering its third and by far its largest growth cycle. Photo: Getty / Unsplash

Panda bonds, financing and the political-economic chain reaction

Among the technical considerations surrounding gas supply contracts, financing is crucial yet often underestimated. Although the technical details of the Moscow–Beijing gas arrangement remain undisclosed, speculation has grown over whether China might authorise extensive onshore renminbi issuance through so-called Panda bonds, to be used explicitly for the construction of PoS-2. If renminbi proceeds could then be converted into roubles via official exchange operations or robust market mechanisms, the project’s financing model would shift substantially. This could deliver more predictable capital for construction, allow faster capacity deployment, strengthen China’s leverage in price negotiations and potentially increase Chinese-centred debt exposure within the project’s capital structure.

Quantitatively, a plausible “critical mass” for such an issuance would be in the tens of billions of RMB (roughly 20–60 billion RMB or 3–8 billion USD), aimed initially at direct PoS-2 financing. Fully replacing capital expenditures would require far more substantial programmes.

Yet considerable constraints and risks make large-scale change unlikely for now. China’s domestic bond-market depth remains unproven for major Russia-linked issuances. Investor appetite – especially among insurers – may be limited by the threat of secondary sanctions. Converting renminbi into roubles at scale would require currency arrangements that expose both sides to legal and counterparty risk. And crucially, insurance, specialist contractors and pipeline expedition services still depend heavily on global enterprises; domestic alternatives exist but would consume time and capital.

Ultimately, the success of using Panda bonds would depend on issuance scale, currency-conversion mechanisms and the role of Chinese banks and insurers. If issuance remains small or its use ambiguous, its impact will be limited and largely symbolic. These constraints reduce the likelihood that Panda-based financing will meaningfully advance the project.

Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin in Moscow, May 2025. Photo: CC BY 4.0 licence

Conclusion: what the EU – and Estonia – should keep in mind

Against a backdrop of geopolitical tension and rivalry, great-power energy behaviour is increasingly shaped by autonomy and regionalisation, with cooperation largely confined to like-minded partners. Meanwhile, LNG markets in the coming years are likely to be shaped by three key forces: the surge in global production capacity, China’s growing market share and its deepening cooperation with Russia – especially if Panda bonds are deployed at scale.

Market participants may also move away from the US Henry Hub benchmark, favouring other pricing points, and may increasingly choose alternative regulatory frameworks such as English or Singaporean law. The combined effect could increase market polarisation, tighten Sino-Russian alignment and deepen the divergence between Asian and European markets.

For the European Union – and especially for Estonia – this means turning uncertainty into preparedness: reinforcing gas storage, preserving diversified supply channels and ensuring competitive pricing. Estonia’s small gas market also opens a different opportunity: domestic demand could potentially be met through expanded biomethane production, while overall consumption could be moderated through energy-efficiency measures and further electrification backed by renewables.

But this alone will not suffice. In the near term, remaining demand will still need to be covered by LNG imports. Here Estonia’s advantage lies in regional integration. Closer coordination with the other Baltic states and Finland would create the scale necessary for more competitive LNG cargo pricing. To fully realise this, legal and regulatory frameworks must be strengthened to support a functional joint Baltic-Finnish gas market. This would bolster Estonia’s supply security against potential volatility while keeping energy costs manageable for end-users.