In November, the European Commission presented the Digital Omnibus package, an ambitious initiative intended to simplify and align the EU’s overlapping digital regulations, from data protection to artificial intelligence and cybersecurity.

The initiative has already sparked intense debate. At its core lies a fine line between simplification – which eases the burden – and deregulation – which removes the brakes. The commission’s own messaging has done little to dispel doubts. Its press release went out of its way to insist that the package upholds “Europe’s highest standards” of rights and protections – an unusual reassurance for a bloc that prides itself on precisely that. Yet only weeks earlier, the commission president Ursula von der Leyen had called not merely for simplification but for deregulation as the way forward, a contrast that has prompted questions about what the Omnibus is really designed to deliver.

What pushed the Commission in this direction, however, cannot be explained by internal politics alone. The turning point came in the spring, on a stage thousands of kilometres away: Ohio, and the spectacle billed as “Liberation Day”.

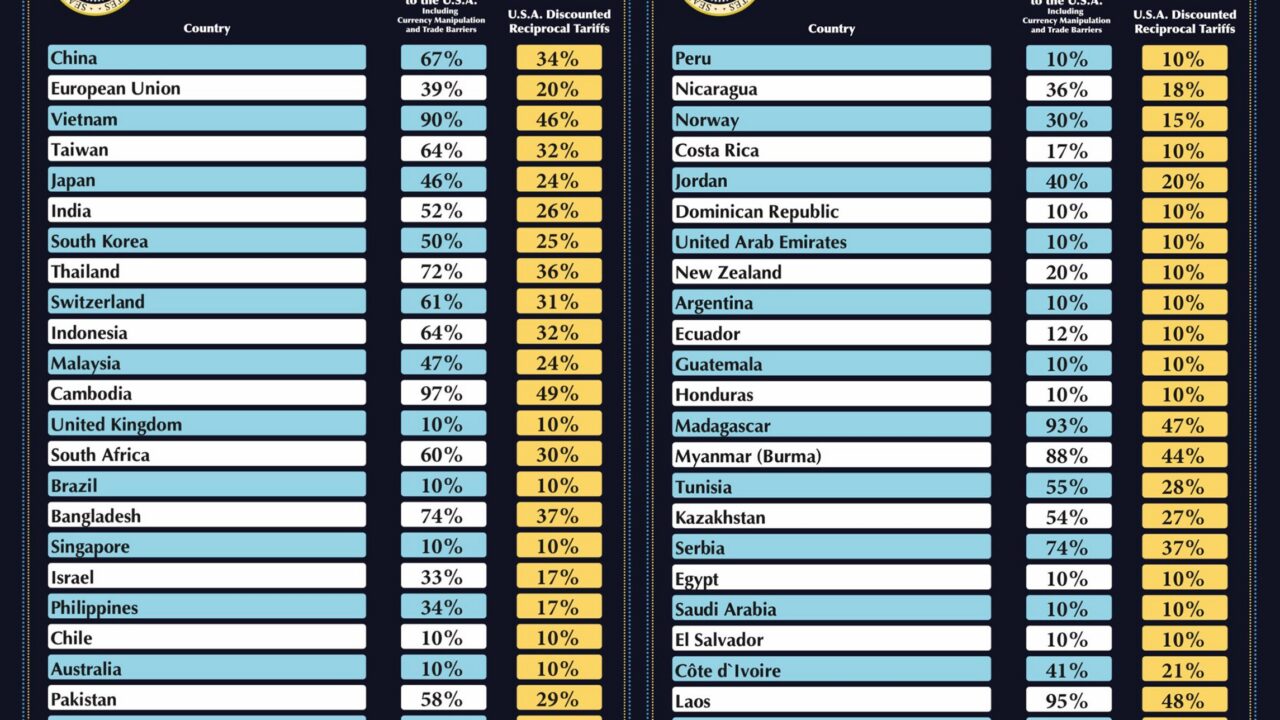

Supporters waited for Donald Trump to unveil the tariffs – trumpets blaring, flags everywhere – when he lifted a comically oversized cardboard sign. Amid the jumble of names, one line stood out: “European Union, 20%.” The three words, predictable as they were, sent shockwaves across the globe, along with a blunt message: the rules of the transatlantic relationship had changed.

That shock did not remain confined to trade. It spilled directly into the EU’s digital agenda, as Trump’s administration launched a sustained campaign to undermine the bloc’s regulatory ambitions. What began as a tariff threat quickly expanded into a full-spectrum effort – from public warnings to diplomatic pressure – aimed at forcing Brussels to soften or delay its tech rules.

What pushed the Commission in this direction, however, cannot be explained by internal politics alone. The turning point came in the spring, on a stage thousands of kilometres away: Ohio, and the spectacle billed as “Liberation Day”.

Supporters of US President Donald Trump awaited the tariff announcement – trumpets blaring, flags waving – when he raised a comically oversized cardboard sign. Amid the jumble of names, one line stood out: “European Union, 20%.” Photo: The White House

In an August broadside, Trump vowed to hit any country adopting “digital taxes” or tech regulations targeting US firms with “substantial” tariffs, a threat squarely aimed at the EU’s sweeping Digital Services Act and related proposals. Washington backed the rhetoric with action. The State Department instructed US diplomats in Europe to “build opposition” to the DSA’s content rules and push for their rollback, arguing that EU policies were censoring Americans and punishing US companies.

No tactic was ruled out. Officials even floated the idea of personal sanctions, including visa bans for European regulators enforcing what they labelled the DSA’s “censorship regime”. Trump himself threatened to invoke trade weapons such as Section 301 to “nullify” EU penalties he deemed “unfair”. By late 2025, the White House was openly linking transatlantic trade détente to tech policy, warning that steep tariffs on EU metal exports would remain unless Europe “rebalanced” its digital rulebook to Washington’s satisfaction.

It is in this climate that the Digital Omnibus landed – not as a technical simplification, but as legislation shaped by geopolitical crosswinds blowing at full force. It became less a housekeeping exercise than a stress test of Europe’s constitutional limits.

Loosened definitions, subjective thresholds and sweeping exemptions – whether framed as “pseudonymised” or “innovation-driven” – risk reopening the very loopholes regulators had fought to close. As civil society organisations warn, several proposals would weaken enforcement, blur legal certainty and make fundamental rights harder – sometimes almost impossible – to exercise in practice.

As civil society organisations warn, several proposals would weaken enforcement, blur legal certainty and make fundamental rights harder – sometimes almost impossible – to exercise in practice.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen meeting US President Donald Trump on 27 July 2025 to discuss trade relations between the two economic powers. Photo: Fred Guerdin / European Commission

What the Omnibus ultimately risks is not disorder, but amnesia. Piece by piece, it forgets why Europe wrote these rules in the first place: to keep power accountable, to keep abuses visible, and to prevent individuals from being reduced to raw material.

The question is no longer whether the union can simplify its regulatory framework, but whether it can do so without eroding the principles on which it is built. If the Omnibus becomes the template for crisis-driven reform, Europe may discover too late that, in trying to save the rulebook, it has sacrificed the very protections that made its model worth defending.

What the Omnibus ultimately risks is not disorder, but amnesia. Piece by piece, it forgets why Europe wrote these rules in the first place: to keep power accountable, to keep abuses visible, and to prevent individuals from being reduced to raw material.