In the early 2000s, she explored her options broadly, following what felt both intellectually stimulating and challenging. This led her to a curriculum that combined electronics with biomedical equipment – a decision that offered both technological depth and real-world relevance, something she felt deeply drawn to. Later she obtained TalTech´s masters degree in engineering/industrial management.

Dementjeva said that she was among the few women in her programme. Yet Anna never saw her gender as something that defined her trajectory. “Competence and curiosity – not gender – determine success,” she said.

From practice student to manager

As part of her studies, Dementjeva was required to complete a practical placement. That single requirement became the gateway to a lifetime of professional growth. She chose a manufacturing company called Elcoteq – which later became Ericsson’s Tallinn site – and joined as a young engineer eager to apply her academic foundation to real processes.

Dementjeva stated that the transition from university to industry was remarkably smooth. She quickly saw that engineering was not just theory, but a living, evolving discipline shaped by real products, real constraints and real people. Her first role allowed her to explore technologies, production processes, and collaboration across teams – experiences that laid the foundation for everything she would do in the decades ahead.

Over the years, Dementjeva moved through positions that spanned quality engineering, supply management, manufacturing engineering, order management and planning. Each step taught her something new. Each team revealed another layer of how complex, global production ecosystems function. And each challenge strengthened her clarity about where she could bring real impact.

“Competence and curiosity – not gender – determine success.”

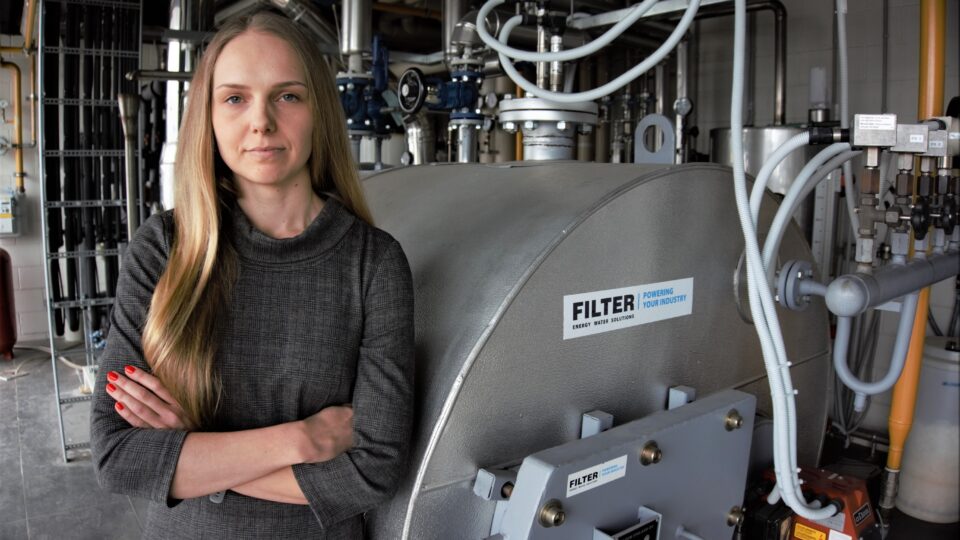

As part of her studies, Dementjeva had to complete a professional internship. That mandatory step marked the beginning of a professional journey spanning decades. She chose to do her internship at the manufacturing company Elcoteq – which later became Ericsson’s Tallinn factory – and started working as a junior engineer to apply the knowledge she had gained at university to real production processes. Photo: Ericsson

Engineer at heart

Although Dementjeva’s titles have shifted from “engineer” to “manager”, she still describes herself as an engineer at heart. “My engineering background guides my decisions every day,” she explained. Logical reasoning, system thinking, and analytical problem-solving remain the backbone of how she leads.

Today she manages the Configuration and Product Substitution department – a team of 25 specialists responsible for product data, product changes and lifecycle coordination across Ericsson’s global operations. It’s a role that requires precision, structure, cross-site alignment and the ability to foresee the ripple effects of every technical decision.

She said that leading specialists rather than engineers wasn’t a dramatic shift for her. The core of the work is still analytical, detail-oriented and deeply collaborative. She sees the similarities more than the differences. “Regardless of title, people work with complex processes that require responsibility and analytical thinking,” she noted. Her role, therefore, is not to micromanage expertise – it is to create an environment where people can perform at their best.

Dementjeva’s leadership philosophy didn’t emerge overnight. When she first stepped into management, she began with a strong focus on processes and technical accuracy. That was, after all, the world she knew best. But experience changed her view of what leadership truly requires. „Over time I’ve learned that effective leadership is about trust, communication, and empowering people. While my engineering mindset still guides my decisions, supporting team growth and collaboration has become the most important part of my role.“

Having spent more than 21 years in one global company gives her a unique advantage: she sees the organisation not as separate units but as an integrated system. This long-term perspective allows her to anticipate how decisions affect processes both locally and globally. It helps her build teams with not only current tasks in mind, but future readiness.

“My engineering background guides my decisions every day.”

In Dementjeva’s view, universities and companies play a major role in shaping attitudes. Young women are more likely to see engineering as a realistic and attainable career choice when they have access to more hands-on collaboration opportunities, more visible female role models, and early exposure to technical environments. Photo: Ericsson

Women in engineering – breaking assumptions through example

If one theme runs through Dementjeva’s story, it is this: female engineers don’t need to fit a stereotype to belong in the field. They help redefine the field simply by being in it.

She has worked in teams where she was one of the few women, but she never felt she had to perform differently because of her gender. “I’ve never experienced a situation where being a woman meant I had to prove myself in some special way,” she noted.

Yet she is fully aware that stereotypes persist in society. One of the most harmful myths, she says, is that engineering is lonely, mechanical, or unsuited for women. “Engineering is highly creative and collaborative,” Dementjeva emphasised – and her career across multiple departments illustrates just that. From supply chains to configuration management, engineering work thrives on communication, teamwork and an ability to see the bigger system.

She believes that universities and companies play a critical role in changing perceptions. More hands-on collaboration, visible female role models, and early exposure to technical environments can help young women picture themselves in engineering roles. Supportive workplaces matter too – places where women are not seen as exceptions, but as part of the normal talent pool.

Her own presence in leadership positions challenges the outdated idea of what an engineer “should look like”. She represents a new normal, one where women can build long-term, influential careers in technical fields without having to justify their belonging.

“I’ve never experienced a situation where being a woman meant I had to prove myself in some special way.”

* The article was produced in collaboration with the Engineering Academy. One of the Engineering Academy’s goals is to increase the proportion of girls in engineering fields.