His work blended field sampling with modelling to reveal not just where the plastics are, but also how they arrive, accumulate, and what they mean for local ecosystems.

The research makes clear that microplastics largely enter the Baltic through land-based pathways. “The main sources we found were rivers and wastewater treatment plants. Rivers carried the bulk of the microplastics, about 76%, while treatment plants added around 24%.” This means riverine discharge is the dominant driver of microplastic influx into the region, while wastewater infrastructure, though secondary, still plays a significant role.

These inputs immediately shape the distribution. Concentrations peak in coastal zones, especially at river mouths and near wastewater outflows, while levels decrease farther offshore. Hydrodynamic forces – winds, currents, upwelling, and downwelling – then redistribute particles across the water column, sometimes spreading them widely, sometimes pushing them into narrow zones of accumulation. Coastal areas remain hotspots due to constant inputs and localized water movement, whereas the open sea dilutes pollutants more broadly.

Unexpected hotspots and ecosystem risks

Not all findings matched the expected patterns. Mishra recalled one standout result: “In 2018, we observed unexpectedly high concentrations of microplastics at station 85 in the open sea. This was unusual because, in most cases, higher concentrations were found closer to the coast near source areas.” Such anomalies suggest that mesoscale processes and current dynamics can sometimes trap and concentrate pollutants far from their original sources.

Once in the sea, microplastics interact with both pelagic and benthic systems. Their behaviour depends on particle type and environmental conditions – some remain suspended, while others sink to the seabed. In both cases, organisms encounter them. Marine species ingest plastics directly, confusing them with food, which disrupts feeding efficiency and energy balance. Microplastics also act as vectors for pollutants and microorganisms, carrying harmful compounds into the food web. Aggregation with organic matter and resuspension from sediments keep particles circulating for years, ensuring persistent exposure risks for local ecosystems.

„Rivers carried the bulk of the microplastics, about 76%, while treatment plants added around 24%.”

Methods, challenges and knowledge gaps

To detect and quantify these particles, Mishra’s team relied on manta trawl sampling with a 330 µm mesh. Samples were dried, inspected under a stereomicroscope, and tested with a hot needle to confirm plastic composition. The approach had clear limitations. “The main challenges were that the method only captures larger microplastics above the mesh size, while smaller particles may be missed,” he said. Distinguishing plastics from natural fragments under the microscope was another source of uncertainty.

These challenges mirror broader gaps in scientific understanding. Harmonized, standardized methodologies remain urgently needed so that results are comparable across regions. Biological uptake and trophic transfer are still poorly understood, particularly concerning coloured plastics and fibrous forms that dominate in the Baltic. Short-term variability linked to convergence, divergence, and upwelling events complicates tracking, while deeper layers and sediments remain less studied. Future research, Mishra stressed, must prioritise long-term monitoring and ecosystem-level impacts.

Pathways toward solutions

Despite the daunting picture, the research offered clear directions for action. “Since rivers and wastewater treatment plants were identified as the main contributors, improving filtration in WWTPs and reducing untreated discharges would make a big difference,” Mishra stressed. Stormwater management in urban areas is another critical step, reducing plastics before they reach rivers. Regionally, harmonized monitoring standards between Baltic states would ensure consistency and reliability, while raising public awareness about everyday plastic use could cut inputs at their origin.

Looking ahead, Mishra warned that without intervention, microplastic levels in the eastern Baltic will likely remain high or continue to grow. Seasonal accumulation patterns, episodic spikes driven by hydrodynamics, and the limited outflow of the semi-enclosed sea all exacerbate the risks. Long-term consequences include persistent accumulation in sediments, increasing presence in biota, and rising ecological stress.

Ultimately, Mishra hopes his work will serve both policymakers and the public. “This research directly supports more informed policy decisions and public awareness initiatives in the Baltic region,” he said. By pinpointing sources, pathways, and hotspots, the findings can guide resource allocation for monitoring, mitigation, and cleanup. They also strengthen the scientific foundation of regional action plans and EU-level proposals to reduce plastic use and improve wastewater treatment.

The eastern Baltic, enclosed yet vulnerable, cannot afford inaction. Mishra’s research highlighted that solutions exist – but only if science, policy, and society work together to keep invisible threats from overwhelming the sea.

“Since rivers and wastewater treatment plants were identified as the main contributors, improving filtration in WWTPs and reducing untreated discharges would make a big difference.”

When microplastics enter the marine environment, they come into contact with both pelagic and near-bottom biota. The behaviour of plastic particles depends on their type: some remain in the upper water column, while others sink to the seabed. In both cases, organisms inevitably come into contact with plastic. Photo: Pexels

Germo Väli – Doctoral supervisor, senior researcher at the TalTech Department of Marine Systems

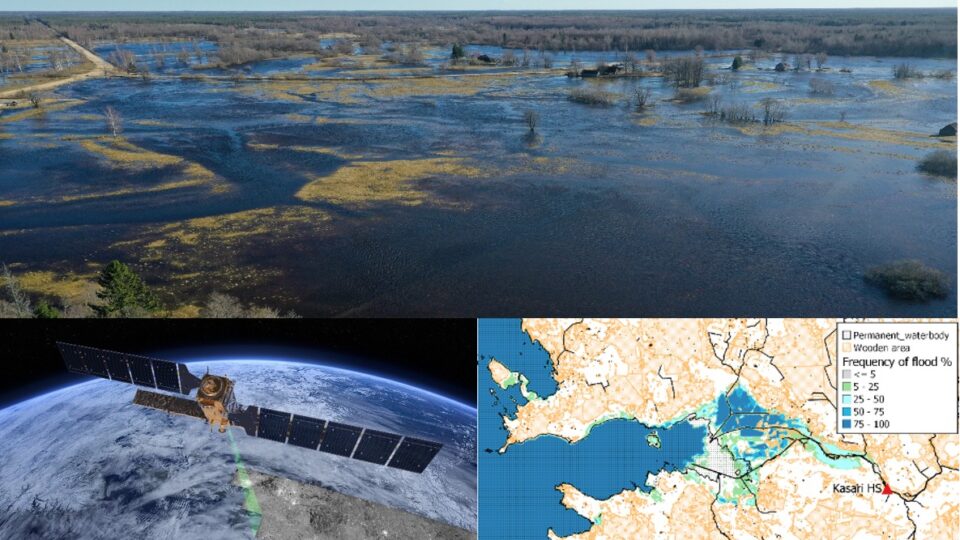

Microplastics have been monitored in the marine environment for only a relatively short time – especially when compared with eutrophication, or nutrient enrichment, which has been studied for decades. Similarly, modelling the transport and distribution of microplastics is still at an early stage. In his doctoral research, Arun Mishra analysed multi-year measurement data, contributed to the development of TalTech’s microplastic model, and applied it to simulate the transport of microplastics in the Gulf of Finland. The dissertation provides the most comprehensive overview to date of the state of microplastics across Estonia’s entire marine area.

The modelling results indicate that most microplastics entering the gulf from land do not reach the open Baltic Sea beyond the Gulf of Finland. In his doctoral work, Arun was also able to highlight the influence of different physical processes on microplastic concentrations, based on both measurement data and model simulations. On the basis of the dissertation results, it is possible to partly explain why microplastic concentrations show such large variability in marine monitoring time series.

Arun’s findings demonstrate how much microplastic is present in the marine environment, which in turn may raise public interest and awareness and thereby reach decision-makers. The model used in the doctoral research still requires further development, but such extensive simulation capacity plays a very important role in designing cost-effective mitigation measures.

If society wishes to prevent the amount of microplastics in the sea from increasing, measures must be implemented to stop microplastics from entering the marine environment in the first place. In other words, a very large proportion of the microplastics that reach Estonia’s marine area or the Baltic Sea as a whole remain there. Technologies for removing microplastics at wastewater treatment plants are being developed, but the point at which microplastics can be completely removed from wastewater is still a long way off. Reducing pollution therefore requires raising public awareness – plastic litter left in the environment breaks down into smaller pieces, a significant share of which eventually reaches the marine environment as micro- or macroplastics.

Researchers can, of course, take steps to ensure that policymakers pay greater attention to the microplastics problem. Universities can present research results to the wider public, draw decision-makers’ attention to the issue of microplastics, and involve policymakers in discussions. The role of scientists is to provide policymakers with information both on the scale of the problem and on the effectiveness of possible measures. To this end, it is necessary to simultaneously improve the modelling and monitoring of microplastic transport in order to provide decision-makers with accurate information that supports practical solutions.